作潮观山海 /

When the Big Pond Changed With the Tides

Public art installation at Liwan Lake Park, in Pantang, Guangzhou, by Wong Zihao and Liu Diancong; in collaboration with Urban Elephant Architects, Guangzhou. Estimated date of completion in August 2025.

When the Big Pond Changed with the Tides (作潮观山海) is a public art installation along the banks of Liwan Lake (荔湾湖), in Pantang (泮塘), Guangzhou city. The installation comprises of three bodies of work: “Tidal Garden” (潮汐花园); “Sea of Mirrors” (海之镜); and “Finding Heron” (寻鹭). Altogether the three works speculate a former tidally activated imagination of the Pantang landscape, recalling the almost-forgotten histories and cultures of a place that once shape-shifted with the changing tides. The installations invite the public to step into a tidal landscape where reality and illusion, fact and myth, and observation and imagination meet.

1. Tidal Garden / 潮汐花园

There was once a marvelous tidal garden in the grounds of the Changshou Monastery (长寿寺), outside of the western gate Saikwan (西关) of Guangzhou’s old walled city. A pond in the temple garden was connected by channels to the Pearl River, and the diurnal ebbing and flowing riverine tides continuously shaped and reshaped the garden scenery. When the tide went down low, rock features in the garden stood out tall from the surrounding pond bed alluding to the heavenly Sumeru mountains from Buddhist cosmology. In the hightide, the mountains sank beneath the sea resembling the elusive Penglai islands, the mythical abode of the eastern immortals. All around, outside the garden, lychee and longan trees drank heartily from the mudflat ponds that they grew out of, producing fragrant floral scents in the fruiting season. It was said that the rhythmic sounds of the shifting tides in the garden could lead the listener to enlightenment. Yet today, this inventive tidal garden remains lost to history, long demolished since the year 1905.[1]

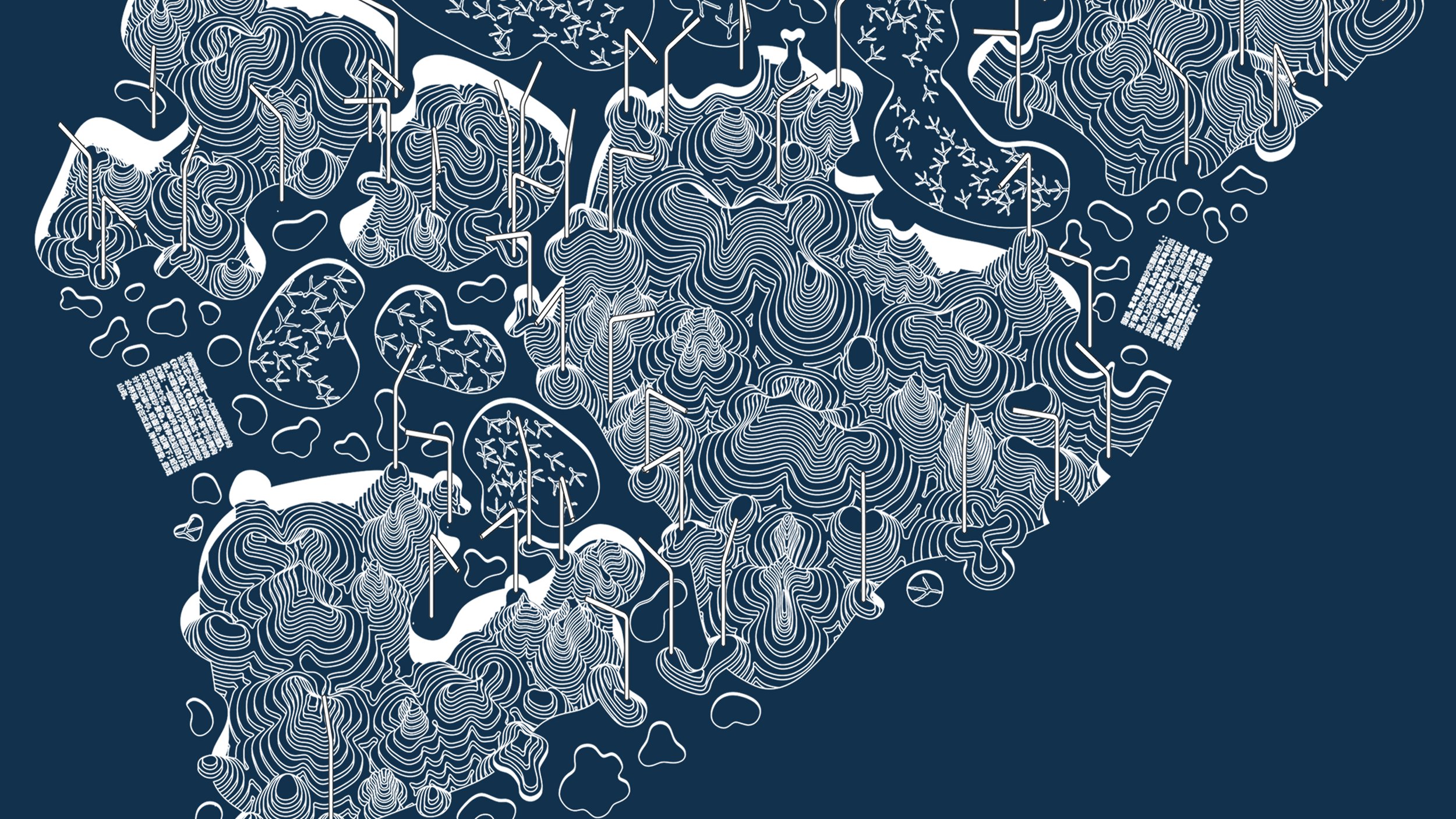

Along the banks of the big lake, we stood and looked (on most times remotely from numerous photographs taken of the site as we designed from our Singapore studio, and a couple more times being there in person on various expeditions to Pantang) and tried to reimagine the landscape when it once changed with the tides. How wonderful would it be if we could reinhabit some of Guangzhou’s historical tidal places, like the magical monastery garden of tides recounted to us through the architectural historians Li Rui and Feng Jiang’s writings. We speculated with their historical reconstruction of the lost tidal garden and wondered if there might be a chance to reactivate a semblance of these shapeshifting landscape experiences at the big pond (that is, the lake at Lychee Creek). In the studio, we began to trace the outlines of water puddles and tidal pools, and carefully stitched the drawings into a composition, building up into hills and valleys. The result was variously reminiscent of a miniature landscape, an architectural model, a concrete topography, a stone dais or a low tea table. The textual accounts of Changshou’s monastic meditative landscape of shapeshifting mountains and islands began to take new form; there it was—the historical tidal garden speculatively (re)constructed through drawing.

And so, we continued to imagine anew.

In the middle of a clearing of trees—in a serene place where people might stop, sit and daydream—sits a low concrete dais: flat and solid as a large garden rock. A miniature topography of hills and valleys is contoured into the stone surface; it is an architectural landscape of recesses and pits, both shallow and deep, resembling a map or plan drawing of a tidal garden—in the making. The children have gathered around the large stone garden to watch the ponds trickle away, little by little, going from wet to dry. A girl points out the peak of Mount Sumeru, whereas her granny suggests another to be the magical island of Penglai. Where the water has totally drained out, islands shapeshifted to mountains. At certain times of the day (past dawn and near dusk, perhaps) automated copper pipes gush out with water to fill up garden, and the tides return and move back up inland twice a day. Then it is that the mountains transform once again into islands, as their bases recede beneath the water.

A boy scoops water from the tidal pool with his hands, splashing and wetting the stone dais. Tiny footprints magically emerge where it is wet. It is the feet of birds. “Look grandpa,” the boy shouts in excitement. “Where are the homes of these birds? Does grandpa know if these birds live in the mountains or the islands? Are they friends with the deities residing on Mount Sumeru or the Penglai immortals? Can we go find them?”

[1] Special thanks to Dr. Xu Hao Hao, Associate Professor of Architecture at the South China University of Technology, for pointing us to this direction of research around Saikwan’s former tidal places and cultures. We are appreciative of architectural historian Dr. Li Rui, also from South China University of Technology, for her pointers to our early abstracts. This description of Changshou Monastery’s tidal garden is referenced from the article: Li Rui, and Feng Jiang, “Chan, Garden, and Poetry: The Tidal Sounds in the Changshou Monastery Garden of Canton in the Qing Dynasty”, in Religions 15 (2024): 664.

2. Sea of Mirrors / 海之镜

The boy grabs his grandpa’s hand, and both soon find themselves wondering amidst a trail of mirrors hovering at various heights on an imaginary ground plane. The mirrors reflect the sky and the underside of tree canopies, recalling the myriad patterns of tidal pools that reveal the sea and the sky on the water’s still surface when the tides pull out. The grandpa muses aloud: “I remember in the past herons can be seen flocking in droves to tidelands where I used to live close-by when I was a boy. The birds look for food in the tidal pools. I was told that the herons are found where there is clean water.”

There are also seven special fragments of “ground” floating among the sea of mirrors. Resembling tables, the flat cast-concrete “grounds” reveal their hidden topographies when seen up close: their surfaces are full of shallow indentations. On some evenings after the rain, the moon can be seen reflected in the momentary sky-mirrors accumulated in the “grounds”. People stop and hunch over these “tidal grounds”, taking turns to pour water onto the tables and look carefully into the small mirror-like pools. A group of children stopped to notice a ghostly map (of a long ago Pantang) taking shape in the water. Miniature lakes and building grids form and unform, in a reimagination of the former tidal estuary where figure and ground, architecture and landscape dissolve in a merging of wetness and dryness, water and land. The surrounding park greens magically transform into a speculative geography full of rock pools, and the jostling children mimic the beachside activity of walking the tidal grounds, peering into the watery pools to look for bits and pieces of reflected sky—and fragments of a long forgotten tidally activated Pantang.

“Looks like a city—but which city is this?”, one of them asked. “How come the water has seeped into the buildings? Fortunately, we have proper drainage now. Perhaps this is an old map.” Another exclaimed, “Hey, how come there are little bird feet walking through the wet places?” The boy and his grandpa from before joined in the excitement: “Where are the birds going? My grandpa says they are herons’ feet; we just need to find where there is clean water!”

3. Finding Heron / 寻鹭

The heron is the lord of tidal and riverine landscapes: not only is it attracted to clean water sources where it feeds from, it builds its nest high up in the trees of mangrove forests. Indeed, the heron is one with the landscape: like the intertidal that is neither land nor water but both; and “a place for shellfish that are half-fish, half-flesh; half-stone, half-living-thing”, the magical heron is a being that can walk on ground, wade in water, and fly into the air.[2] As such its mystical abilities—being able to transcend the three realms of earth, sea, and heaven—invokes the bird’s affinities with the sagely and divine beings hidden in the more-than-earthly places high up in the mountains or set amidst the sea.

“Where will we find the herons?” The children asked the adults they met who stopped by to look at the tidal pools. “Maybe not yet? We might need to wait some more. Perhaps they might return when the tides come back to the place?” Yet perhaps the children do not know that the tides will not be returning any time soon. “But we can wait. We can learn to wait.”

And so we continue to search for the herons. “Finding Herons” is our proposal for waiting: that is to make time for nature, or rather like the tidal landscape, to make our urban selves more attuned to the time of nature. A bench beckons that people stop, sit and view the lake. On the ground, beneath their feet, the herons’ footprints end their journey (or is it the start?)—the imprints accumulating in the floor tiles into puddles in the rainy season. Where there is clean water there you will find the herons. Some of the imprints are beginning to show signs of mossy growth. The tiles are embedded with seeds, waiting for water, waiting for their time to grow. Perhaps there is no art work. Perhaps there is only the art of slowing down, keen observing, and patiently waiting that we have to learn. “Where is the herons, grandpa?”

[2] Linda Cracknell and Owain Jones, “A Conversational Essay on Tides by Linda Cracknell and Owain Jones”, Tidal Cultures, 7 June 2014, http://tidalcultures.wordpress.com/a-conversational-essay-on-tides-by-linda-cracknell-and-owain-jones/.